From the Item Bank |

||

The Professional Testing Blog |

||

Equating Test Forms for FairnessNovember 5, 2015 | |Co-authored by: Reed Castle, Ph.D. and Vincent Lima Certification examination programs often have more than one examination form (set of questions, or items) in use at a time, and they require routine updates. The exam forms represent the same content, but have different items. As new items come into use, they may be easier or harder than the first set of items. As a result, exam forms can have varying degrees of difficulty. These variations need to be taken into account when reporting scores and pass/fail decisions over time and exam forms. When developing and maintaining a credible certification program, one of the overriding themes is “fairness.” If a program is being fair, candidates are being treated in a consistent and reasonable manner. A typical process for developing an exam has sequential steps, which are something like this:

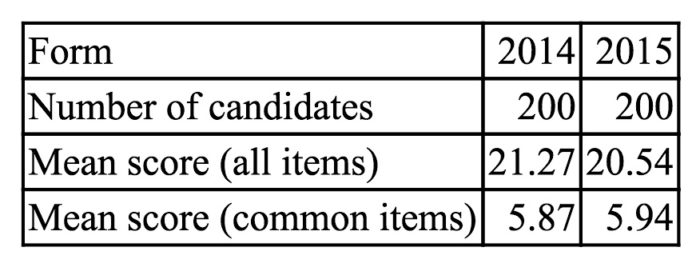

After the first form is developed and scored, examination maintenance includes more item writing, item review, item statistics generation, and equating. The equating process is required to assure fairness across examination forms. The technical explanation for equating is to reconcile group ability differences with exam form difficulty differences. An example may be good at this point. In 2014 a new exam program was developed following steps 1 to 7 above. In 2015, a new form was created, which had some items in common with the initial, 2014 form, and many new, different items. So Steps 8 and 9 are used when we are creating a new exam form. The purpose of the new form (2015) was to change some of the items from the 2014 exam, in part so that those who had taken the 2104 exam didn’t see all the same items. Because items are changed, it is critical to assure fairness with respect to the cut-score. The two forms (2014 and 2015) varied slightly in difficulty and that difference had to be accounted for on the new form to assure fairness to candidates across different forms. Below is a sample table for a 30-item test for 2014 and 2015. The average test score for 2014 was 21.27, and for 2015 it was 20.54. Notice that 2015 is a lower average score, which suggests the new 2015 form is more difficult – assuming the cohort of candidates in 2015 had the same knowledge and skills, on average, as the 2014 cohort. To check that assumption we compare their performance on the common items. If the average score on the common items is about the same, the assumption is confirmed. But what if the new cohort had, say, a lower average score on the common items? Perhaps the best-prepared candidates tested in 2014 and the new group was slightly less well prepared. That would explain, to some extent, the lower average score on the 2015 form. That has to be taken into account in equating so that everyone has to clear the same bar. If we look at the common item mean in this case, we see that the 2015 cohort (mean=5.94) appears about equal or maybe slightly more knowledgeable than the 2014 (mean=5.87) cohort.

What do we know? The 2015 form is more difficult than the 2014 form. The ability of the two groups is similar. So we need to see if the cut-score used in 2014, from the passing score study, is still applicable. In this example, the 2014 cut-score was 22 questions out of 30 correct for passing. Applying a linear equating methodology the new cut-score for the 2015 form should be 21 out of 30 because the new (2015) form is more difficult. It’s worth noting that equating can sometimes be done in advance. If a test includes pilot (unscored) items, the performance of the new form can be estimated in advance. This allows for programs that offer year-round testing to report scores on the spot without waiting for the new passing score to be confirmed. Depending on various factors, different methods can be used to select a fair cut point or passing score. Equating is a process that allows us to reconcile differences between exam forms of varying difficulty. It allows organizations to create a new passing standard on a new form without incurring the expenses associated with an SME meeting. Most importantly, it assures fairness in scoring. Tags: Certification, examination program, Subject Matter ExpertCategorized in: Industry News |

||

Comments are closed here.